MLB LOSES PILLAR OF HONESTY

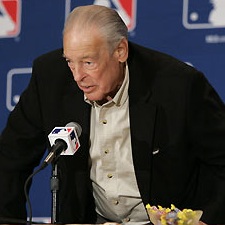

Thursday, December 30th, 2010Bill Lajoie was one of the most remarkable men I ever encountered in Major League Baseball. One reason for that status was he was one of the most honest men I ever met in Major League Baseball.

I don’t mean he fell short of being 100 percent honest while others didn’t. With Lajoie it was the other way around. He just didn’t seem capable of lying, or even telling a little fib.

Lajoie died Tuesday at the age of 76. Cause of death wasn’t immediately known, but he died in his sleep at his home in Osprey, Fla., said a statement from the Pittsburgh Pirates, the last of six organizations he worked for.

Lajoie was general manager of only one of those teams, but it was his choice not to take the job with another team after he left Detroit in 1990. He would have been welcomed in many different front offices.

“I did interview for four other jobs and I was offered three of the jobs but I turned them down,” Lajoie said in a telephone interview last month. “So I obviously didn’t want to be a general manager. My wife had died the year before and my kids were in school. There was a lot of stress in that job.”

Instead Lajoie had a succession of jobs as special assistant or senior adviser to other general managers in Atlanta, Milwaukee, Boston, Los Angeles and Pittsburgh. It was in Detroit, though, that Lajoie achieved his finest moment.

I don’t refer to the Tigers’ World Series championship in 1984, Lajoie’s first season as general manager. Rather I’m talking about 1988 and the Fred Lynn episode.

Lajoie made a deal with Baltimore for Lynn Aug. 31, hoping the left-hand hitting outfielder could help the Tigers maintain the two-game division lead they had over Boston at the time of the trade.

For Lynn to be eligible to play in the post-season should the Tigers make it, he had to be in Detroit by midnight that night. The Players Association later challenged the rule, but in the end the matter became moot because the Tigers finished a game behind the Red Sox.

But in the immediate aftermath of the trade, when the Tigers were still in first place, Lajoie had a decision to make.

He knew that Lynn technically had not arrived in Chicago on his chartered jet from Anaheim, where the Orioles were playing, by midnight.

He knew that the plane had not entered Chicago air space until 10 minutes after midnight.

Lajoie could have said that Lynn had beaten the deadline and, an official in the commissioner’s office said, the office would have accepted his word. But Lajoie chose to be honest.

“He didn’t get there,” Lajoie admitted the next day. “They were over the city limits about 10 after 12.” Asked why he didn’t fudge the time, Lajoie said, “I just felt a rule’s a rule. There’s no sense playing with it. That’s the rule and we’ll live by it.”

I doubt that any other baseball executive would have acted in a similar manner. His act of honesty was so impressive that I wrote about it, and the story appeared on the front page of The New York Times.

Joseph Mehan read the story. He was chief of public information for Unesco (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in this country. Viewing Lajoie’s action as ”a very unusual gesture” and ”an extraordinary act of honesty,” Mehan sent the story to Unesco’s headquarters in Paris, recommending Lajoie for an award.

In August 1989 the International Committee for Fair Play, a part of Unesco, selected Lajoie to receive an honorary diploma and, for some reason, notified him through the United States Olympic Committee.

”When I saw the letterhead,” Lajoie said at the time, ”I thought they wanted me to make a big donation to the Olympic committee.”

Lajoie was scheduled to receive the award the following Oct. 30 at a ceremony in Paris, but he didn’t get there. The Tigers refused to pay for the trip.

A year later Lajoie ended his seven-year tenure as the Tigers’ general manager.

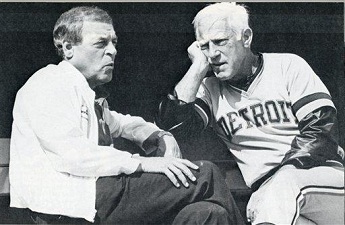

“I didn’t want to be the Detroit general manager,” Lajoie said when I spoke with him last month, explaining that he gave up the job because “I couldn’t get along with Jim Campbell anymore.”

“I didn’t want to be the Detroit general manager,” Lajoie said when I spoke with him last month, explaining that he gave up the job because “I couldn’t get along with Jim Campbell anymore.”

Campbell was the Tigers’ president whom Lajoie had replaced as general manager on the decision of the owner, John Fetzer.

Two veteran general managers, Pat Gillick and Andy MacPhail, kept recommending him for general manager vacancies, Lajoie said, but he asked them to stop.

Lajoie said he was prepared to take the San Francisco job when Peter Magowan was in the process of becoming the Giants’ principal owner before the 1993 season.

“I had my stuff ready to go,” he recalled, “and then Magowan told me three things I had to do. I told him you don’t have to pay me $400,000 to answer the phone.”

That was another way in which Lajoie was different from other general managers. Most others would have grabbed the job just to be employed and earning a salary.

“He had a lot of integrity,” Jim Leyland said on the telephone Wednesday. Leyland, the Tigers’ manager, shared a barracks suite with Lajoie in the mid-1970s when Lajoie was the club’s scouting director and Leyland was a minor league manager. “He was a great teacher for me. He was my teacher as well as my boss. He saw things I didn’t. He knew how to fill out a team. He knew how to get pieces that fit the puzzle.”

How about this piece? Ten days before the end of spring training in 1984 Lajoie acquired Willie Hernandez from Philadelphia to be the Tigers’ closer. Hernandez converted all 32 save opportunities he had and won the Cy Young and most valuable player awards. The Tigers won 35 of their first 40 games and didn’t stop winning until the World Series was over.

That team was also filled with players Lajoie, as scouting director, had been responsible for finding and drafting: Jack Morris and Dan Petry, who between them won 37 games; Lance Parrish, Alan Trammell, Lou Whitaker and Kirk Gibson, whom he stole from the National Football League.

As general manager, Lajoie made his last brilliant move the signing of a player who had been playing in Japan. In his first season, 1990, Cecil Fielder hit 51 home runs.

While Lajoie received credit for the Hernandez trade, he also was foolishly criticized in retrospect for a trade he made in 1987. On Aug. 12 of that season, Lajoie traded for Doyle Alexander. He sent Atlanta a minor leaguer named John Smoltz. But Alexander compiled a 9-0 record and was instrumental in Detroit’s division championship.

Lajoie acknowledged that he was asked about the trade but said, “It’s just one of those things that has come up from time to time. But it doesn’t bother me.”

A minor league player, Lajoie was considered a great evaluator of talent. No statistical analyst was he. In fact, the title of his book, written with Anup Sinha and published earlier this year, sums up his philosophy: Character Is Not a Statistic: The Legacy and Wisdom of Baseball’s Godfather Scout Bill Lajoie.

Dave Eiland, who was the Yankees’ pitching coach the past three years, said in a radio interview last week that he was surprised that the Yankees fired him and didn’t know why they did.

Dave Eiland, who was the Yankees’ pitching coach the past three years, said in a radio interview last week that he was surprised that the Yankees fired him and didn’t know why they did.

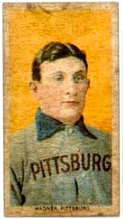

What to do? An order of nuns, the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Baltimore, had their hearts in the right place when they put up for auction a valuable baseball card, but their hearts were jilted when the winner of the auction failed to come forward and actually pay for the card.

What to do? An order of nuns, the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Baltimore, had their hearts in the right place when they put up for auction a valuable baseball card, but their hearts were jilted when the winner of the auction failed to come forward and actually pay for the card.

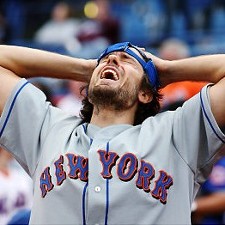

That statement doesn’t require a talented translator. Put simply, don’t expect the Mets to spend any money this winter.

That statement doesn’t require a talented translator. Put simply, don’t expect the Mets to spend any money this winter.