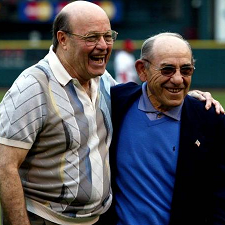

YOGI AND JOE, JUST TWO KIDS

Sunday, September 27th, 2015Joe Garagiola grew up at 5446 Elizabeth Avenue in the Italian immigrant Hill section of St. Louis. Yogi Berra grew up directly across the street at 5447. “He was my best friend,” Garagiola told me. “I’d come out of the house and if I sat on my porch long enough here he comes.”

I called Garagiola last Thursday to talk about his childhood with his buddy Lawdie, formerly known as but never called Lawrence. Berra had died about 36 hours earlier, a fact so overwhelming that Garagiola was not prepared to believe it even though Larry Berra, the oldest of Yogi’s three sons, had called to tell him minutes after Yogi died.

When did you last talk to him? I asked Garagiola.

“I haven’t talked to him in a while,” said Garagiola, at 89 nine months younger than the 90-year-old Berra.

“It’s been a tough week,” Garagiola said. “I got calls on Monday that a couple of friends died.”

“I did not need that piece of news,” he added, speaking of Berra’s death. “Had he been sick? That’s a shocker. It’s sad news but it’s reality. He was my best friend. I can’t remember not knowing him. He was a great guy to grow up with. We’ll miss him. Baseball will miss him.”

Recalling the young Berra, Garagiola said, “Even as a kid he was a great player. He could hit the ball when he was 10. He could always hit. I remember a game at Roosevelt High School. The manager of the other team was riding him something fierce. There were two hills beyond the outfield, and pretty soon he hit one on top of the second hill. As he rounded third he said to the guy who was riding him. ‘How do you like that one?’ That was the only time I ever heard him say something to somebody. He was always polite, never gave you the evil eye.”

Berra was “very popular at the playground,” Garagiola said, and “could play any sport.” He said Berra would always be the first player chosen in pickup games. That went for street games, too. “That’s where you found out about a kid – on the street. Wherever he went – and I went with him – everybody knew him.”

Garagiola recalled one other Berra trait. “He always had time for people,” he said.

Garagiola recalled one other Berra trait. “He always had time for people,” he said.

No official cause of Berra’s death was given, but from a description of his health problems I was given by a close friend of many years it seemed likely that congestive heart failure was at least a contributing factor. His friend said he also suffered terrible back pain.

In his 18 years as an all-star catcher and sometimes outfielder, the squat, 5-foot, 7 ½-inch Berra was not a role model for anyone who wanted to epitomize physical beauty. Some people, in fact, said he resembled a gnome. Post-retirement, though, Berra became engrossed with exercise, thanks to John McMullen, long-time neighbor in Montclair, N.J., and one-time owner of the Houston Astros and employer of Berra as a coach.

“John put him on a diet and got him exercising every day,” Fay Vincent, the former baseball commissioner, related. “He got him to quit smoking. He lost weight and gave up smoking. John had a big influence on Yogi.”

McMullen, who died in 2005, and Berra seemed to be an unlikely couple, but McMullen’s wife, Jacqueline, said,” Yogi latched onto John in the best terms. He gravitated to John and relied on John a lot. They came here every Christmas eve and we’d have cocktails.”

McMullen, who died in 2005, and Berra seemed to be an unlikely couple, but McMullen’s wife, Jacqueline, said,” Yogi latched onto John in the best terms. He gravitated to John and relied on John a lot. They came here every Christmas eve and we’d have cocktails.”

Jackie McMullen and Carmen Berra were close friends until Mrs. Berra died last year after having been married to Yogi for 65 years. Now Mrs. McMullen is the only member remaining from the Montclair quartet.

“She was so responsible for Yogi’s career,” Mrs. McMullen said, not meaning that Carmen hit any of his 358 home runs or drove in any of his 1,430 runs batted in. “Yogi depended on her completely.”

Berra, though, did all right on his own and was especially adept in baseball matters. He was far more intelligent and knew a lot more than he got credit for. And I had an experience with him that demonstrated how quick he was on his feet. It is probably my most vivid personal memory of Yogi.

I don’t remember exactly when it occurred or what question I asked him that prompted Berra to do what he did. He was managing the Mets at the time, and they were playing at Shea Stadium that night. It was before the game, and I was talking to Berra in his office. We started walking through the clubhouse so he could go to the dugout and the field.

I asked what I guess – or at least what Yogi thought – was a tough question. As soon as I asked it, Berra stopped walking and said he had left something he needed in his office. Making a U-turn, he headed back to his office. I stayed where we had reached in the clubhouse and waited for Berra to return. And waited and waited and waited.

After I don’t know how many minutes, I realized I had been had. Berra hadn’t forgotten anything. He didn’t want to answer my question, and that was his way of avoiding it. He had another exit from his office, and he used it. He took another path to the dugout and left me standing alone in the middle of the clubhouse. And some people thought Yogi was dumb.

Another memorable moment occurred in 1985, though in this one Berra was not the central figure. He was more a supporting actor. His son, Dale, was the leading actor.

It was August, and I was working with another New York Times reporter, Michael Goodwin, on a series of articles about cocaine in baseball. It was the summer of drug trials in Pittsburgh, and Dale Berra, then a 28-year-old Yankees’ third baseman, was deeply implicated as a witness who would testify about his acquisition and use of cocaine.

The four-part series, which would become the runner-up for a Pulitzer Prize, was running in the Times that week. Seeing Berra in the Yankees’ clubhouse before a game, I asked him if he had told Yogi about his involvement with cocaine and the trial. He said he had not.

Dale, I said, speaking more like a parent than a reporter because I knew how I would feel if it were my son, the article about you will be in the newspaper this week. Do you want your father to find out about you and cocaine by reading about it or directly from you? He mumbled something about telling Yogi, but I wasn’t convinced and I never found out what he did or how Yogi reacted to the news, however he learned it.

His former teammates and colleagues loved to tell Yogi stories. McMullen had one, too.

His former teammates and colleagues loved to tell Yogi stories. McMullen had one, too.

“One day we were in the room reading,” Brown once told me. “I had to take an exam when I got back to medical school that fall so I was reading ‘Boyd’s Pathology.’ Yogi was reading a comic book of some sort. We both finished about the same time and Yogi asked, ‘How did yours come out?’”

Mike Ferraro was a member of the Yankees’ coaching staff with Berra and became a chronicler of Berra’s bon mots, including:

“We were ordering jackets from a guy in California and I asked Yogi if he wanted any. He said, ‘Order me a navy blue and a navy brown.’”

“Dale was watching a Steve McQueen movie on television sometime after McQueen died and Yogi came in. He said: ‘Gee, that’s Steve McQueen. He must have still been alive when he made that movie.’”

“We were playing golf in Florida and Yogi was talking about putting. He said: ‘Ninety percent of the balls that fall short of the hole don’t go in. The other 10 percent, the wind blows them in.’”

Many such remarks are attributed to Berra, but they are the creation of others. It’s an easy exercise to embellish the legendary literature of the former player, coach, manager, three-time most valuable player and Hall of Famer:

Yogi gets home, and Carmen tells him, “I saw ‘Dr. Zhivago’ this afternoon.” Yogi asks her, “What’s wrong with you now?”

Did that happen?

“No, that wasn’t true,” he told me, a broad grin nevertheless revealing his own enjoyment of the story. “That’s false. That is false.”

How about the one about a restaurant where Berra supposedly remarked, “It’s too crowded; nobody goes there anymore.”

“I said that,” he acknowledged.

Then there was this exchange heard and related by Fay Vincent at Larry Doby’s funeral in 2003.

Ralph Branca, the former major league pitcher, said to Berra, “It’s very nice of you to come to Doby’s funeral.” Berra replied, “I go to your funeral so you’ll come to mine.”

THIS ROSE HAS NEVER SMELLED SWEET

The end is nigh for Pete Rose. That is, the end of the Pete Rose saga is near.

Rose met with Commissioner Rob Manfred last Thursday in his bid to gain reinstatement to Major League Baseball, which he agreed to leave in 1989 as a result of his betting on games when he was managing the Cincinnati Reds.

Besides his violation of Major League rule 21, which prohibits betting on baseball, Rose has to overcome 15 years of lying about his betting generally and additional years of lying about specifics of his betting, such as his claim that he never placed bets from the manager’s office.

It is so unlikely that Manfred will restore Rose to MLB’s good graces that I refuse to say it can’t happen. I don’t believe it will and I don’t think it should happen, but I’ll be patient and wait for Manfred’s decision, which he said he will make by the end of the calendar year.

His predecessor, Bud Selig, received a Rose application for reinstatement in 1997 and never acted on it, letting it languish in a desk drawer or a file cabinet for 17 or 18 years. Maybe that was Selig’s way of telling Rose this is what you deserve, but more likely it was just Selig’s typical way of dealing with decisions he didn’t want to have to make and preferred to leave to the next guy.

In the great 1967 Dustin Hoffman film “The Graduate” his character Benjamin is embraced by a friend of his parents who wants to give him a piece of priceless advice. It’s one word – plastics. The comparable advice in baseball today is analytics.

In the great 1967 Dustin Hoffman film “The Graduate” his character Benjamin is embraced by a friend of his parents who wants to give him a piece of priceless advice. It’s one word – plastics. The comparable advice in baseball today is analytics.

The New York Daily News is suffering the same plight. On Wednesday, after the owner had failed in his effort to sell the paper, it dismissed about a third of the sports staff, including the sports editor, Teri Thompson, and the long-time baseball writer, Bill Madden, who is a fellow winner of the J.G. Taylor Spink award from the Baseball Writers Association.

The New York Daily News is suffering the same plight. On Wednesday, after the owner had failed in his effort to sell the paper, it dismissed about a third of the sports staff, including the sports editor, Teri Thompson, and the long-time baseball writer, Bill Madden, who is a fellow winner of the J.G. Taylor Spink award from the Baseball Writers Association.