PLAYING A GAME BY ANOTHER GAME’S RULES

Sunday, December 31st, 2017Plenty of people play fantasy baseball so join me as I engage in my own form of fantasy baseball.

Let’s say we get to the end of the regular season and we decided to extend the playoffs and allow all of the teams to participate, no matter their won-lost records or place of finish in the standings, However, we exclude the top two teams in each league, giving them byes to the semi-finals, better known as the league championship series. We pair the other 26 teams by whatever means we would like.

In the first rounds, let’s say, the Orioles (75-87) would play the Athletics (75-87) and the White Sox (67-95) would play the Tigers (64-98) in an American League round, and in the National League the Phillies (66-96) would play the Giants (64-98) and the Reds (68-94) would play the Mets (70-92). These games, either one game or a three-game series, would be played anywhere in the country, wherever there is a suitable baseball facility and preferably where is a likelihood of good weather to avoid snowouts.

The winners of these games or series would not advance to another round. They would just pack their equipment bags and go home. Do not, however, disparage these teams because they are not in the final four.

The entire country would be able to see these games because all of them would be televised, of course, mostly on the many ESPN outlets, because ESPN would be happy to pay the going rate for rights to post-season games. Content counts.

This all sounds silly, doesn’t it, but this is what college football bowl games have become. The thought struck me the other day while I was watching a few minutes of the Pinstripe Bowl at – where else? – Yankee Stadium. Boston College was playing Iowa, and I couldn’t understand why Boston College and Iowa were in a bowl game.

Not that I follow college football closely, if at all, but I figured if this was a bowl game of note – or of my youth – I would have heard something about these teams and what a great matchup this was.

Well, I looked up the teams’ records and found, if nothing else, the teams appeared to be evenly matched, each having compiled a 7-5 record during the season.

That record, though, was not the bare minimum that a team needed to qualify for a bowl game. Six is that number, and I learned in my research of this year’s bowl games that three teams that won six games did not receive a bowl invitation: Buffalo, Western Michigan and the University of Texas at San Antonio.

On the other hand, 78 teams received invitations to fill 78 spots. That is a startling number for us who haven’t been paying attention.

Did anyone watch Middle Tennessee (6-6) beat Arkansas State (7-4), 35-30, in the Camellia Bowl; Marshall (7-5) defeat Colorado State (7-5), 31-28, in the New Mexico Bowl; Louisiana Tech (6-6) crush SMU (7-5), 51-10, in the Frisco Bowl; Georgia State (6-5) down Western Kentucky (6-6), 27-17, in the Cure Bowl and Florida Atlantic (10-3) blow out Akron (7-6), 50-3, in the Cherry Bowl. ESPN televised all of those games except the Cure Bowl, which CBSSN carried.

All it takes to create a bowl game apparently is a sponsor and a TV time slot. Put two 11-man teams in different-color uniforms, blow a whistle and start the clock. Team names on the uniform shirts help but obviously are not necessary.

As in baseball, team names matter in the N.F.L. Fans wouldn’t go for a post-season game between teams with New England and Cleveland on their shirts. But college? Make up names and ESPN and the fans apparently will go for it.

One more thing. Come up with a catchy name. I wouldn’t suggest the Cereal Bowl.

AFTER BLANK BALLOT, WHAT NEXT?

After my infamous blank Hall of Fame ballot last year, I seriously considered an even more striking gesture this year. Having absolutely nothing to do with the blank ballot, I seriously considered giving up voting for the Hall of Fame altogether.

Before taking up that issue, though, I want to get back to the blank ballot and the reaction to it, especially from a jerk of a television commentator named Casey Stern.

Stern had a radio show and thought it would be great fun to ridicule me for submitting a blank ballot. Stern, however, was either too lazy or too dumb to do his homework.

He reacted as if my blank ballot was the first ever submitted in a HOF vote. Had he cared to find out and was not out just to have childish fun at my expense, he would have learned that my blank ballot was not the first submitted last year. He also could have found out from Ryan Thibodaux, the master of HOF voting record keeping, that eight blank ballots had been cast in the previous five years.

That information, though, would have spoiled Stern’s play day. When I tried to reach Stern to enlighten him, I was told he was on vacation, and he never returned my calls. This is a class guy, an announcer who was once so careless between innings of a playoff game that he uttered a notorious “M.F.” into an open microphone. As I said, a real class guy.

Now about that blank ballot, if memory serves me correctly, three former players were elected – Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines and Ivan Rodriguez. If I had voted for anyone, I would not have voted for any of that trio.

I have been clear in my position on cheaters. I don’t vote for them. Whether or not they have been caught using steroids or other PEDS, Bagwell and Rodriguez have long been associated with steroids. Raines was an admitted cocaine user. Cocaine might not do for a player what steroids do, but they are and have been illegal, and Raines testified under oath that he began sliding headfirst because he kept a packet of cocaine in his back pocket and didn’t want to mess it up by sliding on it. Honesty on the witness stand does not excuse a player’s use of illegal drugs.

So much for last year’s ballot. As I said, there wasn’t going to be a ballot this year. As I wrote here recently, I don’t think any writers should be voting for the Hall of Fame. Jane Forbes Clark, its chairman and gatekeeper, doesn’t deserve our assistance. Among other reasons for that view, she has kept Marvin Miller out of the Hall for more than 15 years, and that is unconscionable.

So I initially ignored the ballot on my desk, planning to do nothing with it but keeping it for reference when results are announced Jan. 24.

But I bungled my plan, mentioning it to my youngest son and oldest grandson. Separately, they made a strong case for not executing my plan. I kept the ballot on my desk and three days before the deadline invited them to register their best arguments. The result: I voted.

But whom did I vote for? All I can say is, if Edgar Martinez, Chipper Jones, Vladimir Guerrero and Jim Thome ever used steroids, I have never heard about it.

But whom did I vote for? All I can say is, if Edgar Martinez, Chipper Jones, Vladimir Guerrero and Jim Thome ever used steroids, I have never heard about it.

Martinez is the only vote worth explaining. In his first eight years on the ballot, I didn’t vote for Martinez but in retrospect probably think I should have. But then, had I voted for him a year ago, how would Stern have filled his air time?

I was about to seal the envelope when I decided to rethink Jones, Guerrero and Thome. I didn’t want to vote for four; that’s at least one or two too many to be inducted in a single year; it dilutes the honor. But I found it difficult to separate the three additions to my ballot. Many, if not most, writers these days would find it easy to vote for four players. They would find it easy to vote for 10 and more, if they could.

I strongly disagree with that thinking. There is just no way 10 players are good enough to be worthy of induction. Writers who vote for 10 are taking the easy way out. They don’t want to take the time and effort to separate the players into the best and others.

The Hall of Fame should be for the elite of the elite. Otherwise the honor is diluted. We can disagree on whom we think the elite of the elite are, but one thing I know is they aren’t all of the players on voters’ lists of 10.

A few years ago Hall officials pared the voting rolls by about 100, knocking off older writers who were no long active or covering baseball on a daily basis. That was a mistake. I know of several writers who are no longer working but covered the players who are now eligible for the Hall of Fame. They would serve as more intelligent and conscientious voters than many of those voting.

I am in the group of writers who have been stricken from the voting rolls, but I understand I am exempt because I won the J.G. Taylor Spink award about 15 years ago. I frankly don’t think the award warrants an exemption. I’d rather that it gives me the right to designate two or three writers who should still be voting. Maybe that will happen when Miller is elected to the Hall.

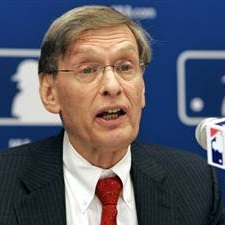

As I have said, Bowman was generating hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of dollars for M.L.B. and its club owners. Why would Selig want to dismiss Bowman and kill that golden goose?

As I have said, Bowman was generating hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of dollars for M.L.B. and its club owners. Why would Selig want to dismiss Bowman and kill that golden goose?